We hype up our favorite bands; We critique on sports and cars; We opine about pop culture. On occasion, will do some creative writing. This is PATHOLOGICAL HATE. Follow us on Twitter: @pathological_h8

Thursday, November 17, 2022

Smart Forfour

The Smart Forfour (stylized as "smart forfour") is a city car (A-segment) marketed by Smart over two generations. The first generation was marketed in Europe from 2004 to 2006 with a front-engine configuration, sharing its platform with the Mitsubishi Colt. The second generation was marketed in Europe from 2014 after an eight-year hiatus, using rear-engine or rear electric motor configurations. It is based on the third-generation Renault Twingo, which also forms a basis for the third-generation Smart Fortwo. A battery electric version was marketed as the EQ Forfour beginning in 2018.

Petrol-powered Forfour was discontinued in 2019 as production of all Smart internal combustion models ended at that time. Production of the EQ Forfour ended in 2021. It was indirectly replaced by the larger Smart #1 crossover.

The car was produced at the NedCar factory in the Netherlands in conjunction with Mitsubishi Motors. This is the same factory that produced Volvo 300 in the 1970s and 1980s and the Volvo S40 in the 1990s. To save production costs, the Smart Forfour shared almost all of its components with the 2003 Mitsubishi Colt. This includes the chassis, suspension and a new generation of MIVEC petrol engines, ranging from the three-cylinder 1.1 L (67 in3) to the four-cylinder with power up to 80 kW (109 PS; 107 hp).

The Smart Forfour was phased out from production in 2006 due to slow sales.

Equipment

Depending on the version, it came equipped with ESP, ABS (standard on all models), 14-inch or 15-inch alloy wheels or, optional, 16-inch ones (17-inch on the Brabus model), safety cell, a panoramic sunroof (or, optional, electric sunroof), height-adjustable driver seat, illuminated glove box, radio/CD-player, fog lights, front and side airbags (standard on all models), alarm, automatic air conditioning, electric front windows, and as options - multifunctional steering wheel, shift paddles, heated front seats, lounge seats, navigation and color display with telephone keypad or DVD navigation with a larger display, CD changer, window bags, rain sensor, automatic lights on the system (in poor visibility), leather package.

Marketing

The sales brochures state that the interior "is designed around the concept of a lounge"; to test this, Top Gear presenters spent 24 hours inside the Forfour. They said they would not buy the car due to its high price and poor driving dynamics compared to its rivals.

Following Smart's initial success for the fortwo in the U.S., and due to surprisingly high popularity in the Forfour, former Mercedes-Benz exec Rainer Schmückle revealed that officials were considering relaunching the car.

Forfour Brabus (2005)

Forfour Brabus is a version of Smart Forfour tuned by Brabus with a turbocharged Mitsubishi 4G15 engine rated 130 kW (177 PS; 174 hp), 27 PS (20 kW; 27 hp) more than the Mitsubishi Colt CZT. It can reach a maximum speed of 221 km/h (137 mph) and accelerate from zero to 100 km/h (62 mph) in 6.9 seconds.

1.0 12v M134 E11 red. I3 1,124 cc 47 kW (64 PS; 63 hp) at 5500 rpm 92 N⋅m (68 lb⋅ft) at 2500 rpm 158 km/h (98 mph) 15.3 s 6.9 l/100 km (41 mpg‑imp) 128 g/km 2005–2006

1.1 12v M134 E11 I3 1,124 cc 55 kW (75 PS; 74 hp) at 6000 rpm 100 N⋅m (74 lb⋅ft) at 3500 rpm 165 km/h (103 mph) 13.4 s 7.0 l/100 km (40 mpg‑imp) 130 g/km 2004–2006

1.3 16v M135 E13 I4 1,332 cc 70 kW (95 PS; 94 hp) at 5250 rpm 125 N⋅m (92 lb⋅ft) at 4000 rpm 180 km/h (112 mph) 10.8 s 7.4 l/100 km (38 mpg‑imp) 138 g/km 2004–2006

1.5 16v M135 E15 I4 1,499 cc 80 kW (109 PS; 107 hp) at 6000 rpm 145 N⋅m (107 lb⋅ft) at 4000 rpm 190 km/h (118 mph) 9.8 s 7.8 l/100 km (36 mpg‑imp) 145 g/km 2004–2006

1.5 16v Brabus M122 E15 AL I4 turbo 1,468 cc 130 kW (177 PS; 174 hp) at 6000 rpm 230 N⋅m (170 lb⋅ft) at 3500 rpm 221 km/h (137 mph) 6.9 s 6.9 l/100 km (41 mpg‑imp) 159 g/km 2005–2006

Diesel engines

1.5 12v cdi 50 kW OM639 DE15 LA red. I3 1,493 cc 50 kW (68 PS; 67 hp) at 4000 rpm 160 N⋅m (118 lb⋅ft) at 1800 rpm 160 km/h (99 mph) 13.9 s 5.8 l/100 km (49 mpg‑imp) 121 g/km 2004–2006

1.5 12v cdi 70 kW OM639 DE15 LA I3 1,493 cc 70 kW (95 PS; 94 hp) at 4000 rpm 210 N⋅m (155 lb⋅ft) at 1800 rpm 180 km/h (112 mph) 10.5 s 5.8 l/100 km (49 mpg‑imp) 121 g/km 2004–2006

The 1.5 L (92 in3) common direct injection (cdi) diesel engine, is a three-cylinder Mercedes-Benz engine derived from the four-cylinder used in the Mercedes-Benz A-Class, and is available with either 68 PS (50 kW; 67 hp) or 95 PS (70 kW; 94 hp).

Transmissions

All models could be equipped with either a 5-speed manual or a 6-speed automatic (Softouch) transmission, except the 1.0-liter version and the Brabus version, which could only use 5-speed manual transmissions.

The second-generation Forfour was jointly developed with Renault, reportedly sharing approximately 70% of its parts with the third-generation Renault Twingo, while retaining the trademark hemispherical steel safety cell, marketed as the Tridion cell. The Fortwo is assembled at Smartville, and the Forfour is manufactured alongside the Renault Twingo 3 in Novo Mesto, Slovenia. Smartville, where the W450 and W451 build series have been manufactured, underwent a 200 million euro upgrade beginning in mid-2013, in preparation for the C453 Fortwo. The second generation Forfour, along with the new Fortwo went on sale in October, shortly after their debuting at the Paris Motor Show

The Smart Fortwo and Forfour is offered with a choice of manual transmission or double-clutch automatic — and no longer with the Getrag automated manual. Both models feature a wider track, overall width increased by 10 cm (over the second generation Fortwo), improved ride and improved noise isolation.

For the third generation, Autoweek projected that Daimler consulted with Ford to learn about Ford's 1.0-litre turbocharged inline 3-cylinder engine, in turn sharing information about its own Euro 6 stratified lean-burn gasoline engines.

The launch model "edition #1" was a limited period version, presented in Tempodrom, Berlin. Delivery is scheduled to commence in November 2014 with the Forfour 52 kW and 66 kW models to follow in December 2014, and twinamic dual-clutch transmission models in the spring of 2015.

Smart Fourjoy concept includes Smart's signature Tridion cell in polished full-aluminium, tail lights integrated in the Tridion cell, spherical instrument cluster, raised smart lettering milled from aluminium on the side skirts, pearlescent white on the bumpers, front bonnet and tailgate; headlamps without a glass cover, U-shaped daytime running lights, LED front and tail lights, transparent petroleum-coloured moulded wind deflector at the top of the front windscreen, on the A-pillars on the sides and on the rear roof spoiler; rear dark chrome seats, a piping-like line with the same petroleum colour as the plexiglass accents on the exterior, instrument panel with convex surface and touch-sensitive operating functions, spherical instrument cluster, single-spoke steering wheel, two smartphones mounted on the dashboard and on the centre tunnel, 55 kW magneto-electric motor, 17.6kWh lithium-ion battery, 22 kW onboard charger, two electrically driven skateboards on the roof, helmets under the rear seats, a high-definition camera.

The vehicle was unveiled at the 2013 Frankfurt Auto Show (without doors and roof).

A concept version, never manufactured, of the Smart Forfour was converted as a plug-in hybrid by third-party vendors. The lithium-ion battery can propel the vehicle up to 84 mph (135 km/h) and last on its own for up to 20 miles (32 km) with an engine that combined a 68 hp (51 kW; 69 PS), 1.5 L (92 in3), three-cylinder turbocharged diesel engine and two high-efficiency permanent-magnet electric motors. It received an award from the Energy Saving Trust for the "Ultra Low Carbon Car Challenge" project.

In 2013, Daimler projected it would produce an electric version of the Smart Forfour during the second generation of production, for launch in 2015. The battery-electric smart forfour electric drive entered mass-production in 2017 at Renault's Novo Mesto plant in Slovenia and was marketed in Europe, competing with other electric city cars such as the MG ZS EV, Renault Twingo Z.E (with which it shares many components), and Volkswagen E-up!, including the SEAT Mii electric and Škoda Citigo-e iV, rebadged versions of the E-up!. In 2019, it was restyled and rebranded to Smart EQ ForFour, after Chinese automobile manufacturer Geely took a stake in Daimler, becoming a 50–50 partner in Smart, and Smart pivoted to market electric cars only. The EQ ForFour was discontinued in early 2022.

It used a rear-mounted 60 kW (80 hp) electric motor with a peak torque of 160 N⋅m (120 lbf⋅ft) and is fitted with a 17.6 kW-hr battery. The EQ Forfour has a rated consumption of 13.1 kWh/100 km (combined) and achieves 160 km (99 mi) range using the NEDC test cycle, dropping to 130 km (81 mi) on the WLTP cycle. As tested, Autocar had a range of 109 km (68 mi), using "a gentle touring driving style", dropping to 80 km (50 mi) when not driving as carefully. The kerb weight of the electric forfour is 1,200 kg (2,600 lb), approximately 225 kg (496 lb) heavier than an equivalent petrol-powered forfour.

Model Years Type/code Power, torque@rpm

Forfour 45 kW 2015–2017 999 cc (61.0 cu in) I3 60 PS (44 kW; 59 hp)@?, ?@?

Forfour 52 kW 2014–2019 999 cc (61.0 cu in) I3 71 PS (52 kW; 70 hp)@?, 91 N⋅m (67 lbf⋅ft)@2850

Forfour 66 kW 2014–2019 898 cc (54.8 cu in) I3 turbo 90 PS (66 kW; 89 hp)@?, 135 N⋅m (100 lbf⋅ft)@2500

Forfour Brabus 2016–2018 898 cc (54.8 cu in) I3 turbo 108 PS (79 kW; 107 hp)@?, 175 N⋅m (129 lbf⋅ft)@2500

Electric motor

Model Years Type/code Power, torque@rpm

EQ Forfour 2017–2021 synchronous electric motor 82 PS (60 kW), 160 N⋅m (118 lbf⋅ft)

Volkswagen Golf Plus

The Volkswagen Golf Plus is a car that was manufactured by Volkswagen between 2004 and 2014. As a five-seater compact MPV (C-segment), it was developed as a taller alternative to the Golf hatchback and positioned below the seven-seater Touran in Volkswagen's product catalogue, the vehicle is based on the Golf Mk5, riding on the PQ35 platform. An alternative appearance package was sold as the Volkswagen CrossGolf in 2006. Throughout its life cycle, it has been sold alongside the Golf Mk5 and Golf Mk6.

In 2014, the Golf Plus was replaced by the MQB-based Golf Sportsvan.

The Golf Plus was presented to the public at the Bologna Motor Show in December 2004. It is 95 mm (3.74 in) taller than the Golf Mk5, and 150 mm (5.91 in) shorter than the three-row Touran. It offers higher seating position, and more space in the cabin with an extra 50 litres of boot space at 395 litres, which is expandable to 505 litres by lowering the boot floor. The rear seats can slide by 160 mm and folded in a new system, resulting in an almost level luggage space when folded. It also split 60:40, with the middle seat doubling as a fold-down drink table.

Many parts of the Golf Mk5 were also used in the Golf Plus, such as engines, transmissions, headrests and exterior mirrors. In contrast to the normal Golf, standard LED rear lights were used in the Golf Plus, the first in the C-segment.

In December 2008, the facelifted version was revealed at the Bologna Motor Show, featuring a revised front end which seen the introduction of the horizontally aligned band front grille and new headlights with daytime running lights, aligning its styling to the Golf Mk6. The revised variant went on sale in early 2009. It retains a largely similar design of the rear end and the interior. For the first time on the Golf Plus, a parallel parking assistance system called ParkAssist was be offered. A rear-view camera mounted behind the Volkswagen badge was also available as an option.

At the 2006 Paris Motor Show, Volkswagen released the CrossGolf which is a version of the Golf Plus with black-plastic body cladding and slightly increased ride height. Part of the Volkswagen Cross family which also includes the CrossPolo and CrossTouran, it was developed by the Volkswagen Individual division, which also developed the Golf R32.

The CrossGolf is only available in front-wheel drive configuration, and is powered by two petrol engines, 1.6 and 1.4 TSI, and two diesel engines, 1.9 TDI and 2.0 TDI, with outputs ranging from 102 PS (75 kW; 101 bhp) to 140 PS (103 kW; 138 bhp). In the UK, this model is badged as Golf Plus Dune and sold with the 1.9 TDI outputting 105 PS (77 kW; 104 bhp).

The facelifted model was introduced in February 2010 at the Geneva Motor Show.

Throughout its production run, seven petrol engine variants are available with an output between 75–170 PS (74–168 hp; 55–125 kW), and five diesel engine variants with an output of 90–140 PS (89–138 hp; 66–103 kW). All diesel engines are equipped with a diesel particulate filter (DPF).

The BlueMotion model was also available with 105 PS (104 hp; 77 kW) and a 5-speed manual gearbox. For efficiency, the BlueMotion model received changes in engine tuning such as lowering the idling RPM. It also received aerodynamic changes such as underbody cover, low-friction tires and lowering the right height by 15 mm (1 in). The third, fourth and fifth gears of the transmission have a longer gear ratio. Average fuel economy was rated at 4.8 L/100 km (21 km/L; 49 mpg‑US).

An LPG variant (BiFuel) was also offered with an output of 98 PS (97 hp; 72 kW) and a 5-speed manual gearbox.

1.2 TSI 1,197 cc I4 CBZA 86 PS (85 hp; 63 kW) 160 N⋅m (16.3 kg⋅m; 118 lb⋅ft) 2010–2014

1.2 TSI 1,197 cc I4 CBZB 105 PS (104 hp; 77 kW) 175 N⋅m (17.8 kg⋅m; 129 lb⋅ft) 2009–2014

1.4 1,390 cc I4 BCA 75 PS (74 hp; 55 kW) 126 N⋅m (12.8 kg⋅m; 92.9 lb⋅ft) 2004–2006

1.4 1,390 cc I4 BUD/CGGA 80 PS (79 hp; 59 kW) 132 N⋅m (13.5 kg⋅m; 97.4 lb⋅ft) 2006–2014

1.4 TSI 1,390 cc I4 CAXA 122 PS (120 hp; 90 kW) 200 N⋅m (20.4 kg⋅m; 148 lb⋅ft) 2007–2014

1.4 TSI 1,390 cc I4 BMY 140 PS (138 hp; 103 kW) 220 N⋅m (22.4 kg⋅m; 162 lb⋅ft) 2006–2008

1.4 TSI 1,390 cc I4 CAVD 160 PS (158 hp; 118 kW) 240 N⋅m (24.5 kg⋅m; 177 lb⋅ft) 2008–2014

1.4 TSI 1,390 cc I4 BLG 80 PS (79 hp; 59 kW) 132 N⋅m (13.5 kg⋅m; 97.4 lb⋅ft) 2006–2014

1.6 1,595 cc I4 BSE/BSF/CCSA 102 PS (101 hp; 75 kW) 148 N⋅m (15.1 kg⋅m; 109 lb⋅ft) 2005–2010

1.6 MultiFuel 1,595 cc I4 CMXA 102 PS (101 hp; 75 kW) 148 N⋅m (15.1 kg⋅m; 109 lb⋅ft) 2010–2014

1.6 BiFuel 1,595 cc I4 CHGA 98 PS (97 hp; 72 kW) (LPG)

102 PS (101 hp; 75 kW) (petrol) 144 N⋅m (14.7 kg⋅m; 106 lb⋅ft) (LPG)

148 N⋅m (15.1 kg⋅m; 109 lb⋅ft) (petrol) 2010–2014

1.6 FSI 1,598 cc I4 BLF/BLP 115 PS (113 hp; 85 kW) 155 N⋅m (15.8 kg⋅m; 114 lb⋅ft) 2004–2007

2.0 FSI 1,984 cc I4 BLR/BVY 150 PS (148 hp; 110 kW) 200 N⋅m (20.4 kg⋅m; 148 lb⋅ft) 2005–2008

Diesel engines

1.6 TDI (CR) 1,598 cc 14 CAYB 90 PS (89 hp; 66 kW) 230 N⋅m (23.5 kg⋅m; 170 lb⋅ft) 2009–2014

1.6 TDI (CR) 1,598 cc 14 CAYC 105 PS (104 hp; 77 kW) 250 N⋅m (25.5 kg⋅m; 184 lb⋅ft) 2009–2014

1.9 TDI (PD) 1,896 cc I4 BRU/BXF/BXJ 90 PS (89 hp; 66 kW) 210 N⋅m (21.4 kg⋅m; 155 lb⋅ft) 2005–2008

1.9 TDI (PD) 1,896 cc I4 BKC/BXE/BLS 105 PS (104 hp; 77 kW) 250 N⋅m (25.5 kg⋅m; 184 lb⋅ft) 2004–2008

2.0 TDI (CR) 1,968 cc I4 CBDC 110 PS (108 hp; 81 kW) 250 N⋅m (25.5 kg⋅m; 184 lb⋅ft) 2008–2009

2.0 TDI (PD) 1,968 cc I4 BKD 140 PS (138 hp; 103 kW) 320 N⋅m (32.6 kg⋅m; 236 lb⋅ft) 2004–2008

2.0 TDI (PD) 1,968 cc I4 BMM 140 PS (138 hp; 103 kW) 320 N⋅m (32.6 kg⋅m; 236 lb⋅ft) 2005–2008

2.0 TDI (CR) 1,968 cc I4 CBDB 150 PS (148 hp; 110 kW) 320 N⋅m (32.6 kg⋅m; 236 lb⋅ft) 2008–2014

Volkswagen Golf Variant

For the first time an estate was produced, being launched in early 1993, and bringing it into line with key competitors such as the Ford Escort and Vauxhall/Opel Astra, which had long been available as estates. The GT variants included a 2.8LVR6 engine, and a convertible launched as the Cabrio (Type 1E).

The Volkswagen Golf Mk4 Variant was introduced in 1999. It was discontinued in 2006, and succeeded in 2007 by the Volkswagen Golf Mk5 Variant. Unlike the Mk3, it was offered in North America with the "Jetta" name with corresponding front styling. The "Jetta Wagon" was used in North America instead of the "Bora" name.

Volkswagen introduced an estate/station wagon version of the fourth-generation car at the 2001 Los Angeles Auto Show[19] as the first A-segment wagon Volkswagen offered in North America — the body style solely manufactured in Wolfsburg. The wagon offered 963 l (34 ft3) of volume with the rear seat up, and wth rear seats were folded provided 1473 l (52 ft3).

In Europe, the estate version was at times marketed as a Golf wagon, either in addition to or instead of the Bora. Other than different front bumpers, fenders, headlights, and hood, the cars were identical. In some countries, VW marketed both Golf Variant and Bora Variant, with the Bora Variant being more upmarket than its counterpart.

The station wagon version of the Golf Mk5 debuted at the International Geneva Motor Show in March 2007 and was marketed as the Golf Variant in the German domestic market, in The United States as the Jetta SportWagen, and in Argentina and Uruguay as the Vento Variant. Designed by Murat Günak, it is more closely related to the Jetta saloon with a shared front fascia design and front doors. It was produced in Puebla, Mexico since April 2007 alongside the similar Jetta with a targeted annual production of 120,000 units.

Volkswagen did not intend to release the station wagon/estate version of the Golf Mk5 until later in its life cycle. Initially, Volkswagen expected the Golf Plus and Touran to be able to cover the station wagon segment left by the Golf, however it was reported that dealers and customers were asking for a replacement instead.

It was facelifted in late 2009, with changes including the front clip and interior from the Golf Mk6, while the remaining is based on the pre-facelifted model. It is marketed as the station wagon version of the Golf Mk6 as it was sold alongside it. The facelifted model was also marketed as the Golf Wagon and Variant in the Canada and Mexico, while it continued to be sold as the Jetta SportWagen in the United States.

A facelifted variant Mk5 Golf Variant model was introduced in 2009 as the Mk6, despite carrying the front fascia, interior styling, and the powertrain from the new Golf, the body shell and underpinnings are based on its fifth-generation predecessor. It is sold in the US as the Jetta SportWagen, in Mexico and Canada as the Golf Wagon and in South America as the Jetta Variant or Vento Variant.

The estate/station wagon of the Golf was revealed at Geneva Motor Show in March 2013. It is marketed as the Golf Variant in Germany and Golf SportWagen in the United States and Canada, replacing the Jetta SportWagen nameplate previously used in the US.

The Golf Estate's loadspace volume has been expanded from the 505 litres of its predecessor to 605 litres (loaded up to the back seat backrest) versus the 380 litres of the Golf hatchback. Loaded up to the front seat backrests and under the roof, the new Golf Estate offers a cargo volume of 1,620 litres (versus the 1,495 litres of the Golf Estate Mk6). The rear seat backrests can be folded remotely via a release in the boot.

Four petrol engines and three diesel engines are available, ranging from 85 PS (63 kW; 84 hp) to 140 PS (103 kW; 138 hp) in the petrol and 90 PS (66 kW; 89 hp) to 150 PS (110 kW; 148 hp) for the diesel engines.

For the first time, the Golf Estate will also be available as a "full" BlueMotion model (with other modifications, including revised aerodynamics). This model uses a 1.6-litre diesel engine producing 110 PS, has a six-speed manual gearbox, and is expected to achieve a combined fuel consumption of just 85.6 mpg (equivalent to 87 g/km of CO2).

The Golf SportWagen is available in S, SE, and GT (Trendline, Comfortline, and Highline in Canada) (GT is SEL in the USA) trim levels. There is also a Golf Estate R, using the same EA888 2.0 engine found in the MkVII Golf R hatchback. The Golf Variant is also built as a rugged version called Alltrack with slightly-raised suspension, body cladding, and all-wheel drive.

Saturday, November 12, 2022

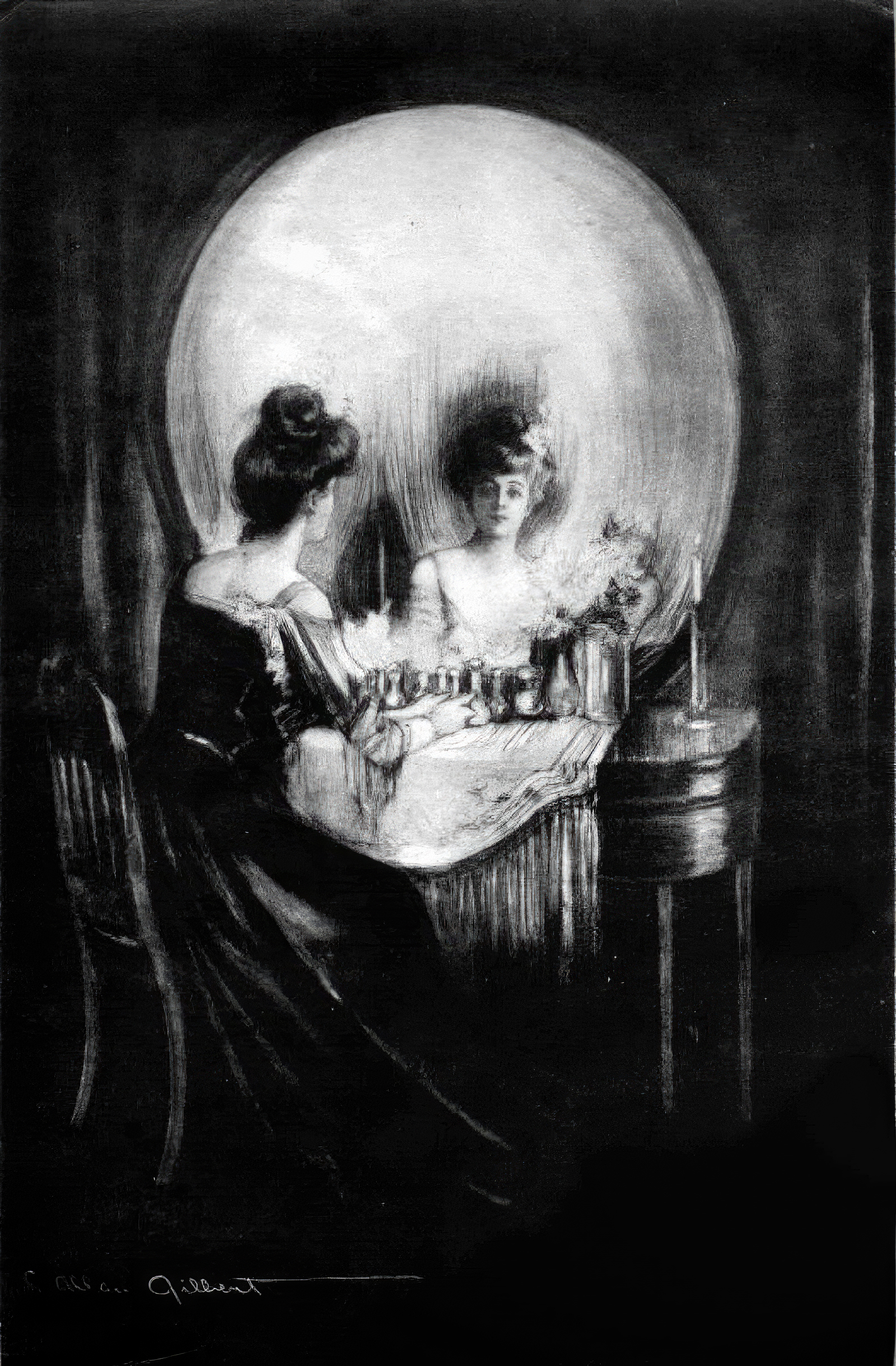

Death Anxiety

Death anxiety is anxiety caused by thoughts of one's own death, and is also referred to as thanatophobia (fear of death). Death anxiety differs from necrophobia, which is the fear of others who are dead or dying.

Psychotherapist Robert Langs proposed three different causes of death anxiety: predatory, predator, and existential. In addition to his research, many theorists such as Sigmund Freud, Erik Erikson, and Ernest Becker have examined death anxiety and its impact on cognitive processing.

Death anxiety has been found to affect people of differing demographic groups as well, such as men versus women, young versus old, etc.

Additionally, there is anxiety caused by death-recent thought-content, which might be classified within a clinical setting by a psychiatrist as morbid and/or abnormal. This classification pre-necessitates a degree of anxiety which is persistent and interferes with everyday functioning. Lower ego integrity, more physical problems and more psychological problems are predictive of higher levels of death anxiety in elderly people perceiving themselves close to death.

Death anxiety can cause a person to become extremely timid or distressed when discussing anything to do with death.

Findings from one systematic review demonstrated that death anxiety features across several mental health conditions.

One meta-analysis of psychological interventions targeting death anxiety showed that death anxiety can be reduced using cognitive behavioral therapy.

Predatory death anxiety arises from the fear of being harmed. It is the oldest and most basic form of death anxiety, with origins in the first unicellular organisms' set of adaptive resources. Unicellular organisms have receptors that have evolved to react to external dangers, along with self-protective, responsive mechanisms made to increase the likelihood of survival in the face of chemical and physical forms of attack or danger. In humans, predatory death anxiety is evoked by a variety of dangerous situations that put one at risk or threaten one's survival. Predatory death anxiety mobilizes an individual's adaptive resources and leads to a fight-or-flight response, consisting of active efforts to combat the danger or attempts to escape the threatening situation.

Predation or predator death anxiety is a form that arises when an individual harms another, physically and/or mentally. This form of death anxiety is often accompanied by unconscious guilt. This guilt, in turn, motivates and encourages a variety of self-made decisions and actions by the perpetrator of harm to others.

Existential death anxiety stems from the basic knowledge that human life must end. Existential death anxiety is known to be the most powerful form of death anxiety. It is said that language has created the basis for existential death anxiety through communicative and behavioral changes. Other factors include an awareness of the distinction between self and others, a full sense of personal identity, and the ability to anticipate the future. The existential psychiatrist Irvin Yalom asserts that humans are prone to death anxiety because "our existence is forever shadowed by the knowledge that we will grow, blossom, and inevitably, diminish and die."

Human beings are the only living things that are truly aware of their own mortality and spend time pondering the meaning of life and death. Awareness of human mortality arose some 150,000 years ago. In that extremely short span of evolutionary time, humans have fashioned a single basic mechanism through which they deal with the existential death anxieties this awareness has evoked: denial. Denial is effected through a wide range of mental mechanisms and physical actions, many of which go unrecognized. While denial can be adaptive in limited use, excessive use is more common and is emotionally costly. Denial is the root of such diverse actions as breaking rules, violating frames and boundaries, manic celebrations, directing violence against others, attempting to gain extraordinary wealth and power, and more. These pursuits are often activated by a death-related trauma, and while they may lead to constructive actions, more often than not they lead to actions that are damaging to self and others.

The term thanatophobia stems from the Greek representation of death, known as Thanatos. Sigmund Freud hypothesized that people express a fear of death as a disguise for a deeper source of concern. He asserted the unconscious does not deal with the passage of time or with negations, which do not calculate the amount of time left in one's life. Under the assumption people do not believe in their own deaths, Freud speculated it was not death people feared. He postulated one does not fear death itself, because one has never died. He suspected death related fears stem from unresolved childhood conflicts.

Developmental psychologist Erik Erikson formulated the psychosocial theory that explained that people progress through a series of crises as they grow older. The theory also envelops the concept that once an individual reaches the latest stages of life, they reach the level he titled as "ego integrity". Ego integrity is when one comes to terms with their life and accepts it. It was also suggested that when a person reaches the stage of late adulthood they become involved in a thorough overview of their life to date. When one can find meaning or purpose in their life, they have reached the integrity stage. In opposition, when an individual views their life as a series of failed and missed opportunities, then they do not reach the ego integrity stage. Elders that have attained this stage of ego integrity are believed to exhibit less of an influence from death anxiety.

Ernest Becker based terror management theory (TMT) on existential views which added a new dimension to previous death anxiety theories. This theory ascertains that death anxiety is not only real, but also people's most profound source of concern. He explained the anxiety as so intense that it can generate fears and phobias of everyday life—fears of being alone or in a confined space. Based on the theory, many of people's daily behavior consist of attempts to deny death and to keep their anxiety under strict regulation.

This theory suggests that as an individual develops mortality salience, or becomes more aware of the inevitability of death, they will instinctively try to suppress it out of fear. The method of suppression usually leads to mainstreaming towards cultural beliefs, leaning for external support rather than treading alone. This behavior may range from simply thinking about death to the development of severe phobias and desperate behavior.

Religiosity can play a role in death anxiety through the concept of fear. There are two major claims concerning the interplay of fear and religion: that fear motivates religious belief, and that religious belief mitigates fear. From these, Ernest Becker and Bronislaw Malinowski developed what is called "Terror Management Theory." According to Terror Management Theory, humans are aware of their own mortality which, in turn, produces intense existential anxiety. To cope with and ease the produced existential anxiety, humans will pursue either literal or symbolic immortality. Religion often falls under the category of literal immortality, but at times, depending on the religion, can also provide both forms of immortality. Through Terror Management Theory, and other death-focused theories, there is a distinct pattern that develops indicating that those who are either very low or very high in religiosity experience much lower levels of death anxiety, meanwhile those with a very moderate amount of religiosity experience the highest levels of death anxiety. One of the major reasons that religiosity plays such a large role in Terror Management Theory, as well as in similar theories, is the increase in existential death anxiety that people experience. Existential death anxiety is the belief that everything ceases after death; nothing continues on in any sense. Seeing how people deeply fear such an absolute elimination of the self, they begin to gravitate toward religion which offers an escape from such a fate. According to one specific meta-analysis study that was performed in 2016, it was shown that lower rates of death anxiety and general fear about dying was experienced by those who went day-to-day living their religion and abiding by its practices, compared to those who merely label themselves as a member of a given religion without living in accord to its doctrines and prescribed practices.

A 2009 study on death anxiety in the context of religion showed that Christians scored lower for death anxiety than non-religious individuals, which supports the main tenets of terror management theory, that people pursue religion to avoid anxiety about death by finding comfort in the ideas about afterlife and immortality. Interestingly, the study also found that Muslims scored much higher than Christians and non-religious individuals for death anxiety. These findings do not support terror management theory, the belief in an afterlife for muslims in the study caused more anxiety than those with no belief in an afterlife. This finding highlights a need for further examination into TMT in the context of different religions/sects as well as the impact of varying beliefs about afterlife on levels of death anxiety.

Martin Heidegger, the German philosopher, on the one hand showed death as something conclusively determined, in the sense that it is inevitable for every human being, while on the other hand, it unmasks its indeterminate nature via the truth that one never knows when or how death is going to come. Heidegger does not engage in speculation about whether being after death is possible. He argues that all human existence is embedded in time: past, present, future, and when considering the future, we encounter the notion of death. This then creates angst. Angst can create a clear understanding in one that death is a possible mode of existence, which Heidegger described as "clearing". Thus, angst can lead to a freedom about existence, but only if we can stop denying our mortality (as expressed in Heidegger's terminology as "stop denying being-for-death").

Paul T. P. Wong's work on the meaning management theory indicates that human reactions to death are complex, multifaceted and dynamic. His "Death Attitude Profile" identifies three types of death acceptance as Neutral, Approach, and Escape acceptances. Apart from acceptances, his work also represents different aspects of the meaning of death fear that are rooted in the bases of death anxiety. The ten meanings he proposes are finality, uncertainty, annihilation, ultimate loss, life flow disruption, leaving the loved ones, pain and loneliness, prematurity and violence of death, failure of life work completion, judgment and retribution centered.

The existential approach, with theorists such as Rollo May and Viktor Frankl, views an individual's personality as being governed by the continuous choices and decisions in relation to the realities of life and death. Rollo May theorized that all humans are aware of the fact that they must one day die, reminiscent of the Latin adage memento mori. However, he also theorized that humans must find meaning in life, which led to his main theory on death anxiety: that all humans face the dichotomy of finding meaning in life, but also confronting the knowledge of approaching death. May believed that this dichotomy could lead to negative anxiety that hindered life, or a positive anxiety that would lead to a life full of meaning and living to one's fullest potential and opportunities. Victor Frankl theorized that through suffering there is meaning and that if one can find meaning in their life even in suffering, they can then aim to reach existentialism.

Other theories on death anxiety were introduced in the late part of the twentieth century. Another approach is the regret theory which was introduced by Adrian Tomer and Grafton Eliason. The main focus of the theory is to target the way people evaluate the quality and/or worth of their lives. The possibility of death usually makes people more anxious if they feel that they have not and cannot accomplish any positive task in the life that they are living. Research has tried to unveil the factors that might influence the amount of anxiety people experience in life.

Humans develop meanings and associate them with objects and events in their environment which can provoke certain emotions. People tend to develop personal meanings of death which could be either positive or negative. If the formed meanings about death are positive, then the consequences of those meanings can be comforting (for example, ideas of a rippling effect left on those still alive). If the formed meanings about death are negative, they can cause emotional turmoil. Depending on the certain meaning one has associated with death, positive or negative, the consequences will vary accordingly. The meaning that individuals place on death is generally specific to them; whether negative or positive, and can be difficult to understand as an outside observer. However, through a Phenomenological perspective, therapists can come to understand their individual perspective and assist them in framing that meaning of death in a healthy way.

A 2012 study involving Christian and Muslim college-students from the US, Turkey, and Malaysia found that their religiosity correlated positively with an increased fear of death.

A 2017 review of the literature found that in the US, both the very religious and the not-at-all religious enjoy a lower level of death anxiety and that a reduction is common with old age.

A 2009 study on death anxiety in the context of religion showed that Christians scored lower for death anxiety than non-religious individuals, which supports the main tenets of terror management theory, that people pursue religion to avoid anxiety about death by finding comfort in the ideas about afterlife and immortality. Interestingly, the study also found that Muslims scored much higher than Christians and non-religious individuals for death anxiety. These findings do not support terror management theory, the belief in an afterlife for muslims in the study caused more anxiety than those with no belief in an afterlife. This finding highlights a need for further examination into TMT in the context of different religions/sects as well as the impact of varying beliefs about afterlife on levels of death anxiety.

A 2019 study further examined the aspect of religiosity and how it relates to death and existential anxiety through the application of supernatural agency. According to this particular study, existential anxiety relates to death anxiety through a mild level of preoccupation that is experienced concerning the impact of one's own life or existence in relation to its unforeseen end. It is mentioned how supernatural agency exists independently on a different dimensional plane than the individual and, as a result, is seen as something that cannot be directly controlled. Oftentimes, supernatural agency is equated with the desires of a higher power such as God or other major cosmic forces. The inability for one to control supernatural agency triggers various psychological aspects that induce intense periods of experienced death or existential anxiety. One of the psychological effects of supernatural agency that is triggered is an increased likelihood to attribute supernatural agency toward causality when dealing with natural phenomena. Seeing how people have their own innate form of agency, the attribution of supernatural agency to human actions and decisions can be difficult. However, when it comes to natural causes and consequences where no other form of agency exists, it becomes much easier to make a supernatural attribution of causality.

Researchers have also conducted surveys on how being able to accept one's inevitable death could have a positive effect on one's psychological well-being, or on one's level of individual distress. A research study conducted in 1974 attempted to set up a new type of scale to measure people's death acceptance, rather than their death anxiety. After administering a questionnaire with questions regarding the acceptance of death, the researchers found there was a low-negative correlation between acceptance of one's own death and anxiety about death; meaning that the more the participants accepted their own death, the less anxiety they felt. While those who accept the fact of their own death will still feel some anxiety about it, this acceptance could allow them to form a more positive perspective on it.

A more recent longitudinal study asked cancer patients at different stages to fill out different questionnaires in order to rate their levels of death acceptance, general anxiety, demoralization, etc. The same surveys administered to the same people one year later showed that higher levels of death acceptance could predict lower levels of death anxiety in the participants.

The death row phenomenon is the distress and anxiety seen in inmates awaiting execution, which can cause an increased risk for suicidal tendencies and psychotic delusions. A contributing factor to this phenomenon is solitary confinement, lack of social interaction, as well as the psychological impact as a result of their crimes. One study collected data on death row suicides from 1978 to 2010 and found the rate of death row suicides to be higher than suicides in the male prison population as well as males in society, regardless of the increase in supervision of death row inmates.

Death anxiety typically begins in childhood. The earliest documentation of the fear of death has been found in children as young as age 5. Psychological measures and reaction times were used to measure fear of death in young children. Recent studies that assess fear of death in children use questionnaire rating scales. There are many tests to study this including The Death Anxiety Scale for Children (DASC) developed by Schell and Seefeldt. However the most common version of this test is the revised Fear Survey Schedule for Children (FSSC-R). The FSSC-R describes specific fearful stimuli and children are asked to rate the degree to which the scenario/item makes them anxious or fearful. The most recent version of the FSSC-R presents the scenarios in a pictorial form to children as young as 4. It is called the Koala Fear Questionnaire (KFQ). The fear studies show that children's fears can be grouped into five categories. One of these categories is death and danger. This response was found amongst children age 4 to 6 on the KFQ, and from age 7 to 10.[45] Death is the most commonly feared item and remains the most commonly feared item throughout adolescence.

A study of 90 children, aged 4–8, done by Virginia Slaughter and Maya Griffiths showed that a more mature understanding of the biological concept of death was correlated to a decreased fear of death. This may suggest that it is helpful to teach children about death (in a biological sense), in order to alleviate the fear.

The connection between death anxiety and one's sex appears to be strong. Studies show that females tend to have more death anxiety than males. In 1984, Thorson and Powell did a study to investigate this connection, and they sampled men and women from 16 years of age to over 60. The Death Anxiety Scale, and other scales such as the Collett-Lester Fear of Death Scale, showed higher mean scores for women than for men. Moreover, researchers believe that age and culture could be major influences in why women score higher on death anxiety scales than men.

Through the evolutionary period, a basic method was created to deal with death anxiety and also as a means of dealing with loss. Denial is used when memories or feelings are too painful to accept and are often rejected. By maintaining that the event never happened, rather than accepting it, allows an individual more time to work through the inevitable pain. When a loved one dies in a family, denial is often implemented as a means to come to grips with the reality that the person is gone. Closer families often deal with death better than when coping individually. As society and families drift apart so does the time spent bereaving those who have died, which in turn leads to negative emotion and negativity towards death. Mothers hold greater concerns about death due to their caring role within the family. It is this common role of women that leads to greater death anxiety as it emphasize the 'importance to live' for her offspring. Although it is common knowledge that all living creatures die, many people do not accept their own mortality, preferring not to accept that death is inevitable, and that they will one day die.

Multiple studies show death anxiety peaking in the early 20s for both men and women, followed by a sharp decline. A 1996 study showed while death anxiety decreased with age, psychosocial maturity was a better predictor of death anxiety than age overall. Higher psychosocial maturity was positively correlated with lower levels of death anxiety.

There are many ways to measure death anxiety and fear. In 1972, Katenbaum and Aeinsberg devised three propositions for this measurement. From this start, the ideologies about death anxiety have been able to be recorded and their attributes listed. Methods such as imagery tasks to simple questionnaires and apperception tests such as the Stroop test enable psychologists to adequately determine if a person is under stress due to death anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder.

The Lester attitude death scale was developed in 1966 but not published until 1991 until its validity was established. By measuring the general attitude towards death and also the inconsistencies with death attitudes, participants are scaled to their favorable value towards death.

One systematic review of 21 self-report death anxiety measures found that many measures have problematic psychometric properties.

Millions of people around the world have died from COVID-19 during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Those who fear that they are more prone to contracting and dying from COVID-19 have higher levels of death anxiety and are more susceptible to general psychological disturbances such as depression, anxiety, stress, and paranoia. Elderly individuals, who were already likely to experience death anxiety outside of a pandemic situation, now find their fear of death largely exacerbated. The fear of dying from COVID-19 has also been one of the leading factors in psychological distress among many countries during the course of the pandemic. It has particularly affected women and those with a lower level of education. During the COVID-19 pandemic, death anxiety has been a large contributor to declining mental wellbeing among those working in helping professions such as nursing and social work.

Death (part two)

Life extension refers to an increase in maximum or average lifespan, especially in humans, by slowing down or reversing the processes of aging through anti-aging measures. Despite the fact that aging is by far the most common cause of death worldwide, it is socially mostly ignored as such and seen as "necessary" and "inevitable" anyway, which is why little money is spent on research into anti-aging therapies, a phenomenon known as the pro-aging trance.

Average lifespan is determined by vulnerability to accidents and age or lifestyle-related afflictions such as cancer, or cardiovascular disease. Extension of average lifespan can be achieved by good diet, exercise and avoidance of hazards such as smoking. Maximum lifespan is also determined by the rate of aging for a species inherent in its genes. Currently, the only widely recognized method of extending maximum lifespan is calorie restriction. Theoretically, extension of maximum lifespan can be achieved by reducing the rate of aging damage, by periodic replacement of damaged tissues, or by molecular repair or rejuvenation of deteriorated cells and tissues.

A United States poll found that religious people and irreligious people, as well as men and women and people of different economic classes have similar rates of support for life extension, while Africans and Hispanics have higher rates of support than white people. 38 percent of the polled said they would desire to have their aging process cured.

Researchers of life extension are a subclass of biogerontologists known as "biomedical gerontologists". They try to understand the nature of aging and they develop treatments to reverse aging processes or to at least slow them down, for the improvement of health and the maintenance of youthful vigor at every stage of life. Those who take advantage of life extension findings and seek to apply them upon themselves are called "life extensionists" or "longevists". The primary life extension strategy currently is to apply available anti-aging methods in the hope of living long enough to benefit from a complete cure to aging once it is developed.

Before about 1930, most people in Western countries died in their own homes, surrounded by family, and comforted by clergy, neighbors, and doctors making house calls. By the mid-20th century, half of all Americans died in a hospital. By the start of the 21st century, only about 20–25% of people in developed countries died outside of a medical institution. The shift away from dying at home towards dying in a professional medical environment has been termed the "Invisible Death". This shift occurred gradually over the years, until most deaths now occur outside the home.

Death studies is a field within psychology. Many people are afraid of dying. Discussing, thinking about, or planning for their own deaths causes them discomfort. This fear may cause them to put off financial planning, preparing a will and testament, or requesting help from a hospice organization.

Different people have different responses to the idea of their own deaths. Philosopher Galen Strawson writes that the death that many people wish for is an instant, painless, unexperienced annihilation. In this unlikely scenario, the person dies without realizing it and without being able to fear it. One moment the person is walking, eating, or sleeping, and the next moment, the person is dead. Strawson reasons that this type of death would not take anything away from the person, as he believes that a person cannot have a legitimate claim to ownership in the future.

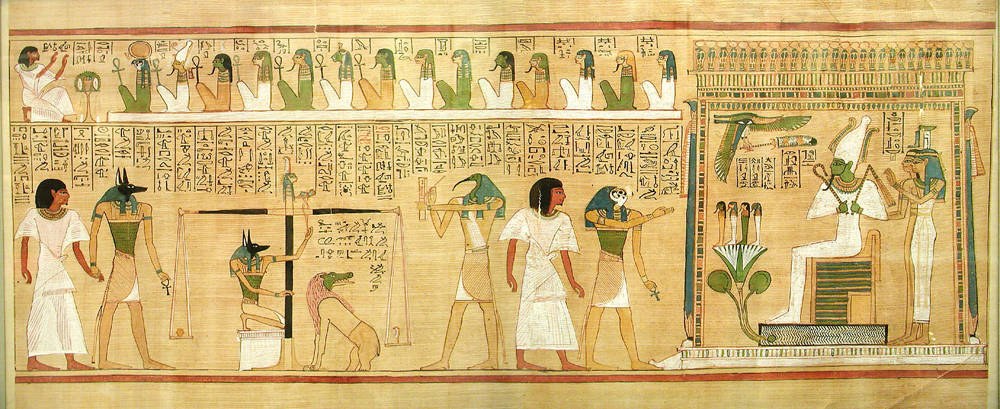

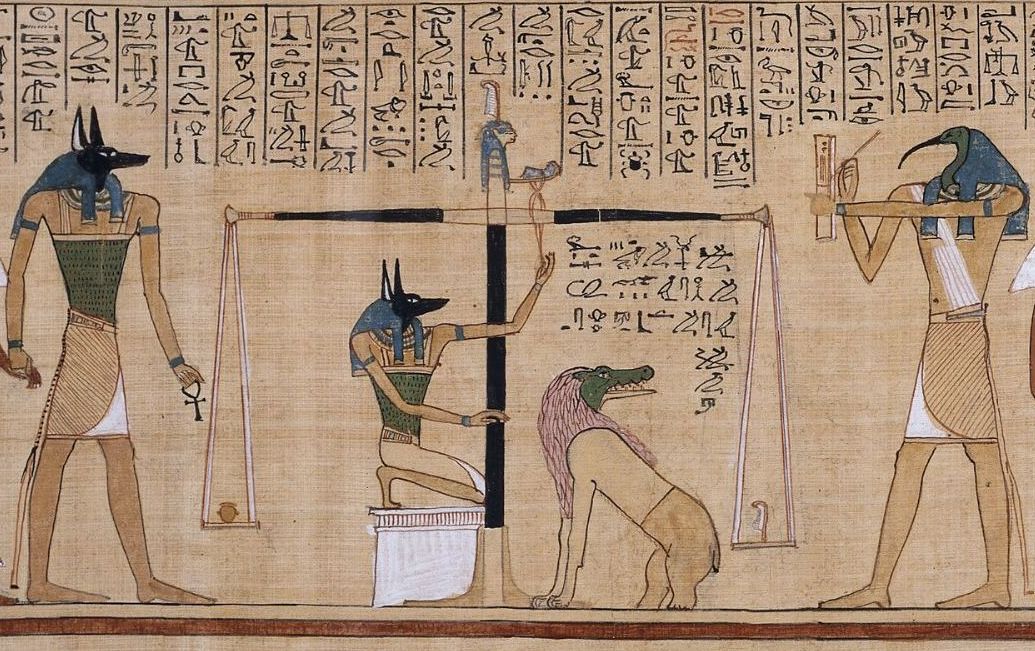

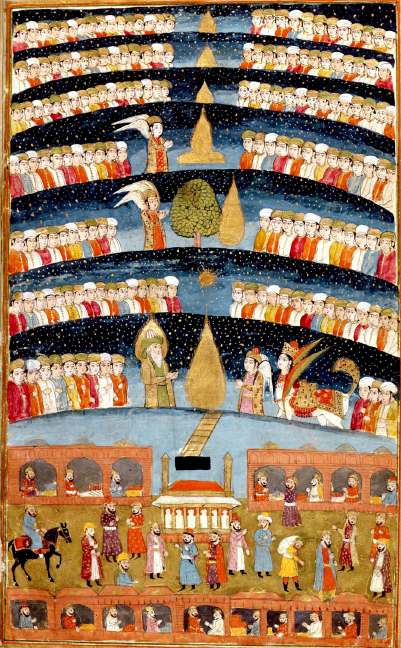

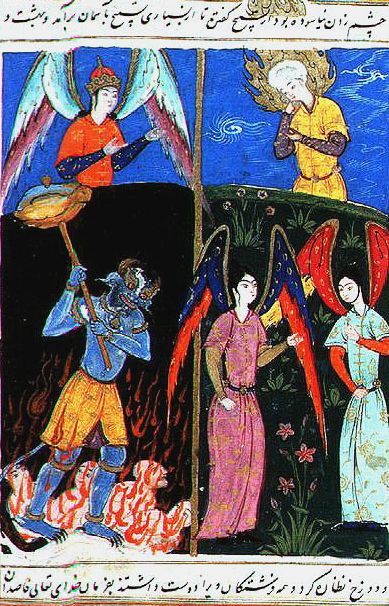

In society, the nature of death and humanity's awareness of its own mortality has for millennia been a concern of the world's religious traditions and of philosophical inquiry. This includes belief in resurrection or an afterlife (associated with Abrahamic religions), reincarnation or rebirth (associated with Dharmic religions), or that consciousness permanently ceases to exist, known as eternal oblivion (associated with Secular humanism).

Commemoration ceremonies after death may include various mourning, funeral practices and ceremonies of honouring the deceased. The physical remains of a person, commonly known as a corpse or body, are usually interred whole or cremated, though among the world's cultures there are a variety of other methods of mortuary disposal. In the English language, blessings directed towards a dead person include rest in peace (originally the Latin requiescat in pace), or its initialism RIP.

Death is the center of many traditions and organizations; customs relating to death are a feature of every culture around the world. Much of this revolves around the care of the dead, as well as the afterlife and the disposal of bodies upon the onset of death. The disposal of human corpses does, in general, begin with the last offices before significant time has passed, and ritualistic ceremonies often occur, most commonly interment or cremation. This is not a unified practice; in Tibet, for instance, the body is given a sky burial and left on a mountain top. Proper preparation for death and techniques and ceremonies for producing the ability to transfer one's spiritual attainments into another body (reincarnation) are subjects of detailed study in Tibet. Mummification or embalming is also prevalent in some cultures, to retard the rate of decay.

Legal aspects of death are also part of many cultures, particularly the settlement of the deceased estate and the issues of inheritance and in some countries, inheritance taxation.

Capital punishment is also a culturally divisive aspect of death. In most jurisdictions where capital punishment is carried out today, the death penalty is reserved for premeditated murder, espionage, treason, or as part of military justice. In some countries, sexual crimes, such as adultery and sodomy, carry the death penalty, as do religious crimes such as apostasy, the formal renunciation of one's religion. In many retentionist countries, drug trafficking is also a capital offense. In China, human trafficking and serious cases of corruption are also punished by the death penalty. In militaries around the world courts-martial have imposed death sentences for offenses such as cowardice, desertion, insubordination, and mutiny.

Death in warfare and in suicide attack also have cultural links, and the ideas of dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, mutiny punishable by death, grieving relatives of dead soldiers and death notification are embedded in many cultures. Recently in the western world, with the increase in terrorism following the September 11 attacks, but also further back in time with suicide bombings, kamikaze missions in World War II and suicide missions in a host of other conflicts in history, death for a cause by way of suicide attack, and martyrdom have had significant cultural impacts.

Suicide in general, and particularly euthanasia, are also points of cultural debate. Both acts are understood very differently in different cultures. In Japan, for example, ending a life with honor by seppuku was considered a desirable death, whereas according to traditional Christian and Islamic cultures, suicide is viewed as a sin. Death is personified in many cultures, with such symbolic representations as the Grim Reaper, Azrael, the Hindu god Yama and Father Time.

In Brazil, a human death is counted officially when it is registered by existing family members at a cartório, a government-authorized registry. Before being able to file for an official death, the deceased must have been registered for an official birth at the cartório. Though a Public Registry Law guarantees all Brazilian citizens the right to register deaths, regardless of their financial means, of their family members (often children), the Brazilian government has not taken away the burden, the hidden costs and fees, of filing for a death. For many impoverished families, the indirect costs and burden of filing for a death lead to a more appealing, unofficial, local, cultural burial, which in turn raises the debate about inaccurate mortality rates.

Talking about death and witnessing it is a difficult issue with most cultures. Western societies may like to treat the dead with the utmost material respect, with an official embalmer and associated rites. Eastern societies (like India) may be more open to accepting it as a fait accompli, with a funeral procession of the dead body ending in an open-air burning-to-ashes of the same.

Much interest and debate surround the question of what happens to one's consciousness as one's body dies. The belief in the permanent loss of consciousness after death is often called eternal oblivion. Belief that the stream of consciousness is preserved after physical death is described by the term afterlife. Neither are likely to ever be confirmed without the ponderer having to actually die.

After death, the remains of a former organism become part of the biogeochemical cycle, during which animals may be consumed by a predator or a scavenger.[64] Organic material may then be further decomposed by detritivores, organisms which recycle detritus, returning it to the environment for reuse in the food chain, where these chemicals may eventually end up being consumed and assimilated into the cells of an organism. Examples of detritivores include earthworms, woodlice and dung beetles.

Microorganisms also play a vital role, raising the temperature of the decomposing matter as they break it down into yet simpler molecules. Not all materials need to be fully decomposed. Coal, a fossil fuel formed over vast tracts of time in swamp ecosystems, is one example.

Contemporary evolutionary theory sees death as an important part of the process of natural selection. It is considered that organisms less adapted to their environment are more likely to die having produced fewer offspring, thereby reducing their contribution to the gene pool. Their genes are thus eventually bred out of a population, leading at worst to extinction and, more positively, making the process possible, referred to as speciation. Frequency of reproduction plays an equally important role in determining species survival: an organism that dies young but leaves numerous offspring displays, according to Darwinian criteria, much greater fitness than a long-lived organism leaving only one.

Extinction is the cessation of existence of a species or group of taxa, reducing biodiversity. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of that species (although the capacity to breed and recover may have been lost before this point). Because a species' potential range may be very large, determining this moment is difficult, and is usually done retrospectively. This difficulty leads to phenomena such as Lazarus taxa, where species presumed extinct abruptly "reappear" (typically in the fossil record) after a period of apparent absence. New species arise through the process of speciation, an aspect of evolution. New varieties of organisms arise and thrive when they are able to find and exploit an ecological niche – and species become extinct when they are no longer able to survive in changing conditions or against superior competition.

Inquiry into the evolution of aging aims to explain why so many living things and the vast majority of animals weaken and die with age (exceptions include Hydra and the jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii, which research shows to be biologically immortal). The evolutionary origin of senescence remains one of the fundamental puzzles of biology. Gerontology specializes in the science of human aging processes.

Organisms showing only asexual reproduction (e.g. bacteria, some protists, like the euglenoids and many amoebozoans) and unicellular organisms with sexual reproduction (colonial or not, like the volvocine algae Pandorina and Chlamydomonas) are "immortal" at some extent, dying only due to external hazards, like being eaten or meeting with a fatal accident. In multicellular organisms (and also in multinucleate ciliates), with a Weismannist development, that is, with a division of labor between mortal somatic (body) cells and "immortal" germ (reproductive) cells, death becomes an essential part of life, at least for the somatic line.

The Volvox algae are among the simplest organisms to exhibit that division of labor between two completely different cell types, and as a consequence include death of somatic line as a regular, genetically regulated part of its life history.

In Buddhist doctrine and practice, death plays an important role. Awareness of death was what motivated Prince Siddhartha to strive to find the "deathless" and finally to attain enlightenment. In Buddhist doctrine, death functions as a reminder of the value of having been born as a human being. Being reborn as a human being is considered the only state in which one can attain enlightenment. Therefore, death helps remind oneself that one should not take life for granted. The belief in rebirth among Buddhists does not necessarily remove death anxiety, since all existence in the cycle of rebirth is considered filled with suffering, and being reborn many times does not necessarily mean that one progresses.

Death is part of several key Buddhist tenets, such as the Four Noble Truths and dependent origination.

While there are different sects of Christianity with different branches of belief; the overarching ideology on death grows from the knowledge of afterlife. Meaning after death the individual will undergo a separation from mortality to immortality; their soul leaves the body entering a realm of spirits. Following this separation of body and spirit (i.e. death) resurrection will occur. Representing the same transformation Jesus Christ embodied after his body was placed in the tomb for three days. Like Him, each person's body will be resurrected reuniting the spirit and body in a perfect form. This process allows the individuals soul to withstand death and transform into life after death.

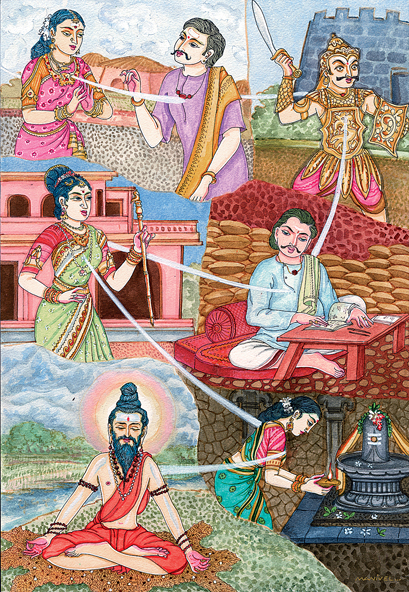

In Hindu texts, death is described as the individual eternal spiritual jiva-atma (soul or conscious self) exiting the current temporary material body. The soul exits this body when the body can no longer sustain the conscious self (life), which may be due to mental or physical reasons, or more accurately, the inability to act on one's kama (material desires). During conception, the soul enters a compatible new body based on the remaining merits and demerits of one's karma (good/bad material activities based on dharma) and the state of one's mind (impressions or last thoughts) at the time of death.

Usually the process of reincarnation (soul's transmigration) makes one forget all memories of one's previous life. Because nothing really dies and the temporary material body is always changing, both in this life and the next, death simply means forgetfulness of one's previous experiences (previous material identity).

Material existence is described as being full of miseries arising from birth, disease, old age, death, mind, weather, etc. To conquer samsara (the cycle of death and rebirth) and become eligible for one of the different types of moksha (liberation), one has to first conquer kama (material desires) and become self-realized. The human form of life is most suitable for this spiritual journey, especially with the help of sadhu (self-realized saintly persons), sastra (revealed spiritual scriptures), and guru (self-realized spiritual masters), given all three are in agreement.

There are a variety of beliefs about the afterlife within Judaism, but none of them contradict the preference of life over death. This is partially because death puts a cessation to the possibility of fulfilling any commandments.

The word "death" comes from Old English dēaþ, which in turn comes from Proto-Germanic *dauþuz (reconstructed by etymological analysis). This comes from the Proto-Indo-European stem *dheu- meaning the "process, act, condition of dying".

The concept and symptoms of death, and varying degrees of delicacy used in discussion in public forums, have generated numerous scientific, legal, and socially acceptable terms or euphemisms. When a person has died, it is also said they have "passed away", "passed on", "expired", or "gone", among other socially accepted, religiously specific, slang, and irreverent terms.

As a formal reference to a dead person, it has become common practice to use the participle form of "decease", as in "the deceased"; another noun form is "decedent".

Bereft of life, the dead person is a "corpse", "cadaver", "body", "set of remains" or, when all flesh is gone, a "skeleton". The terms "carrion" and "carcass" are also used, usually for dead non-human animals. The ashes left after a cremation are lately called "cremains".

Friday, November 11, 2022

Death (part one)

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain death is sometimes used as a legal definition of death. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose shortly after death. Death is an inevitable process that eventually occurs in almost all organisms.

Death is generally applied to whole organisms; the similar process seen in individual components of an organism, such as cells or tissues, is necrosis. Something that is not considered an organism, such as a virus, can be physically destroyed but is not said to die. As of the early 21st century, over 150,000 humans die each day, with ageing being by far the most common cause of death.

Many cultures and religions have the idea of an afterlife, and also may hold the idea of judgement of good and bad deeds in one's life (heaven, hell, karma).

The concept of death is a key to human understanding of the phenomenon. There are many scientific approaches and various interpretations of the concept. Additionally, the advent of life-sustaining therapy and the numerous criteria for defining death from both a medical and legal standpoint, have made it difficult to create a single unifying definition.

One of the challenges in defining death is in distinguishing it from life. As a point in time, death would seem to refer to the moment at which life ends. Determining when death has occurred is difficult, as cessation of life functions is often not simultaneous across organ systems. Such determination, therefore, requires drawing precise conceptual boundaries between life and death. This is difficult, due to there being little consensus on how to define life.

It is possible to define life in terms of consciousness. When consciousness ceases, an organism can be said to have died. One of the flaws in this approach is that there are many organisms that are alive but probably not conscious (for example, single-celled organisms). Another problem is in defining consciousness, which has many different definitions given by modern scientists, psychologists and philosophers. Additionally, many religious traditions, including Abrahamic and Dharmic traditions, hold that death does not (or may not) entail the end of consciousness. In certain cultures, death is more of a process than a single event. It implies a slow shift from one spiritual state to another.

Other definitions for death focus on the character of cessation of organismic functioning and a human death which refers to irreversible loss of personhood. More specifically, death occurs when a living entity experiences irreversible cessation of all functioning. As it pertains to human life, death is an irreversible process where someone loses their existence as a person

Historically, attempts to define the exact moment of a human's death have been subjective, or imprecise. Death was once defined as the cessation of heartbeat (cardiac arrest) and of breathing, but the development of CPR and prompt defibrillation have rendered that definition inadequate because breathing and heartbeat can sometimes be restarted. This type of death where circulatory and respiratory arrest happens is known as the circulatory definition of death (DCDD). Proponents of the DCDD believe that this definition is reasonable because a person with permanent loss of circulatory and respiratory function should be considered dead. Critics of this definition state that while cessation of these functions may be permanent, it does not mean the situation is irreversible, because if CPR was applied, the person could be revived. Thus, the arguments for and against the DCDD boil down to a matter of defining the actual words "permanent" and "irreversible," which further complicates the challenge of defining death. Furthermore, events which were causally linked to death in the past no longer kill in all circumstances; without a functioning heart or lungs, life can sometimes be sustained with a combination of life support devices, organ transplants and artificial pacemakers.

Today, where a definition of the moment of death is required, doctors and coroners usually turn to "brain death" or "biological death" to define a person as being dead; people are considered dead when the electrical activity in their brain ceases. It is presumed that an end of electrical activity indicates the end of consciousness. Suspension of consciousness must be permanent, and not transient, as occurs during certain sleep stages, and especially a coma. In the case of sleep, EEGs can easily tell the difference.

The category of "brain death" is seen as problematic by some scholars. For instance, Dr. Franklin Miller, senior faculty member at the Department of Bioethics, National Institutes of Health, notes: "By the late 1990s... the equation of brain death with death of the human being was increasingly challenged by scholars, based on evidence regarding the array of biological functioning displayed by patients correctly diagnosed as having this condition who were maintained on mechanical ventilation for substantial periods of time. These patients maintained the ability to sustain circulation and respiration, control temperature, excrete wastes, heal wounds, fight infections and, most dramatically, to gestate fetuses (in the case of pregnant "brain-dead" women)."

While "brain death" is viewed as problematic by some scholars, there are certainly proponents of it that believe this definition of death is the most reasonable for distinguishing life from death. The reasoning behind the support for this definition is that brain death has a set of criteria that is reliable and reproducible. Also, the brain is crucial in determining our identity or who we are as human beings. The distinction should be made that "brain death" cannot be equated with one who is in a vegetative state or coma, in that the former situation describes a state that is beyond recovery.

Those people maintaining that only the neo-cortex of the brain is necessary for consciousness sometimes argue that only electrical activity should be considered when defining death. Eventually it is possible that the criterion for death will be the permanent and irreversible loss of cognitive function, as evidenced by the death of the cerebral cortex. All hope of recovering human thought and personality is then gone given current and foreseeable medical technology. At present, in most places the more conservative definition of death – irreversible cessation of electrical activity in the whole brain, as opposed to just in the neo-cortex – has been adopted (for example the Uniform Determination Of Death Act in the United States). In 2005, the Terri Schiavo case brought the question of brain death and artificial sustenance to the front of American politics.

Even by whole-brain criteria, the determination of brain death can be complicated. EEGs can detect spurious electrical impulses, while certain drugs, hypoglycemia, hypoxia, or hypothermia can suppress or even stop brain activity on a temporary basis. Because of this, hospitals have protocols for determining brain death involving EEGs at widely separated intervals under defined conditions.

In the past, adoption of this whole-brain definition was a conclusion of the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research in 1980. They concluded that this approach to defining death sufficed in reaching a uniform definition nationwide. A multitude of reasons were presented to support this definition including: uniformity of standards in law for establishing death; consumption of a family's fiscal resources for artificial life support; and legal establishment for equating brain death with death in order to proceed with organ donation

Aside from the issue of support of or dispute against brain death, there is another inherent problem in this categorical definition: the variability of its application in medical practice. In 1995, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), established a set of criteria that became the medical standard for diagnosing neurologic death. At that time, three clinical features had to be satisfied in order to determine "irreversible cessation" of the total brain including: coma with clear etiology, cessation of breathing, and lack of brainstem reflexes. This set of criteria was then updated again most recently in 2010, but substantial discrepancies still remain across hospitals and medical specialties.

The problem of defining death is especially imperative as it pertains to the dead donor rule, which could be understood as one of the following interpretations of the rule: there must be an official declaration of death in a person before starting organ procurement or that organ procurement cannot result in death of the donor. A great deal of controversy has surrounded the definition of death and the dead donor rule. Advocates of the rule believe the rule is legitimate in protecting organ donors while also countering against any moral or legal objection to organ procurement. Critics, on the other hand, believe that the rule does not uphold the best interests of the donors and that the rule does not effectively promote organ donation.

Signs of death or strong indications that a warm-blooded animal is no longer alive are:

Respiratory arrest (no breathing)

Cardiac arrest (no pulse)

Brain death (no neuronal activity)

The stages that follow after death are:

Pallor mortis, paleness which happens in 15–120 minutes after death

Algor mortis, the reduction in body temperature following death. This is generally a steady decline until matching ambient temperature

Rigor mortis, the limbs of the corpse become stiff (Latin rigor) and difficult to move or manipulate

Livor mortis, a settling of the blood in the lower (dependent) portion of the body

Putrefaction, the beginning signs of decomposition

Decomposition, the reduction into simpler forms of matter, accompanied by a strong, unpleasant odor.

Skeletonization, the end of decomposition, where all soft tissues have decomposed, leaving only the skeleton.

Fossilization, the natural preservation of the skeletal remains formed over a very long period

The death of a person has legal consequences that may vary between different jurisdictions. A death certificate is issued in most jurisdictions, either by a doctor, or by an administrative office upon presentation of a doctor's declaration of death.

There are many anecdotal references to people being declared dead by physicians and then "coming back to life", sometimes days later in their own coffin, or when embalming procedures are about to begin. From the mid-18th century onwards, there was an upsurge in the public's fear of being mistakenly buried alive, and much debate about the uncertainty of the signs of death. Various suggestions were made to test for signs of life before burial, ranging from pouring vinegar and pepper into the corpse's mouth to applying red hot pokers to the feet or into the rectum. Writing in 1895, the physician J.C. Ouseley claimed that as many as 2,700 people were buried prematurely each year in England and Wales, although others estimated the figure to be closer to 800.

In cases of electric shock, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for an hour or longer can allow stunned nerves to recover, allowing an apparently dead person to survive. People found unconscious under icy water may survive if their faces are kept continuously cold until they arrive at an emergency room. This "diving response", in which metabolic activity and oxygen requirements are minimal, is something humans share with cetaceans called the mammalian diving reflex.

As medical technologies advance, ideas about when death occurs may have to be re-evaluated in light of the ability to restore a person to vitality after longer periods of apparent death (as happened when CPR and defibrillation showed that cessation of heartbeat is inadequate as a decisive indicator of death). The lack of electrical brain activity may not be enough to consider someone scientifically dead. Therefore, the concept of information-theoretic death has been suggested as a better means of defining when true death occurs, though the concept has few practical applications outside the field of cryonics.

There have been some scientific attempts to bring dead organisms back to life, but with limited success.

The leading cause of human death in developing countries is infectious disease. The leading causes in developed countries are atherosclerosis (heart disease and stroke), cancer, and other diseases related to obesity and aging. By an extremely wide margin, the largest unifying cause of death in the developed world is biological aging, leading to various complications known as aging-associated diseases. These conditions cause loss of homeostasis, leading to cardiac arrest, causing loss of oxygen and nutrient supply, causing irreversible deterioration of the brain and other tissues. Of the roughly 150,000 people who die each day across the globe, about two thirds die of age-related causes. In industrialized nations, the proportion is much higher, approaching 90%. With improved medical capability, dying has become a condition to be managed. Home deaths, once commonplace, are now rare in the developed world.

In developing nations, inferior sanitary conditions and lack of access to modern medical technology makes death from infectious diseases more common than in developed countries. One such disease is tuberculosis, a bacterial disease which killed 1.8M people in 2015. Malaria causes about 400–900M cases of fever and 1–3M deaths annually. AIDS death toll in Africa may reach 90–100M by 2025.

According to Jean Ziegler (United Nations Special Reporter on the Right to Food, 2000 – Mar 2008), mortality due to malnutrition accounted for 58% of the total mortality rate in 2006. Ziegler says worldwide approximately 62M people died from all causes and of those deaths more than 36M died of hunger or diseases due to deficiencies in micronutrients.

Tobacco smoking killed 100 million people worldwide in the 20th century and could kill 1 billion people around the world in the 21st century, a World Health Organization report warned.

Many leading developed world causes of death can be postponed by diet and physical activity, but the accelerating incidence of disease with age still imposes limits on human longevity. The evolutionary cause of aging is, at best, only just beginning to be understood. It has been suggested that direct intervention in the aging process may now be the most effective intervention against major causes of death.

Selye proposed a unified non-specific approach to many causes of death. He demonstrated that stress decreases adaptability of an organism and proposed to describe the adaptability as a special resource, adaptation energy. The animal dies when this resource is exhausted. Selye assumed that the adaptability is a finite supply, presented at birth. Later on, Goldstone proposed the concept of a production or income of adaptation energy which may be stored (up to a limit), as a capital reserve of adaptation. In recent works, adaptation energy is considered as an internal coordinate on the "dominant path" in the model of adaptation. It is demonstrated that oscillations of well-being appear when the reserve of adaptability is almost exhausted.

In 2012, suicide overtook car crashes for leading causes of human injury deaths in the U.S., followed by poisoning, falls and murder. Causes of death are different in different parts of the world. In high-income and middle income countries nearly half up to more than two thirds of all people live beyond the age of 70 and predominantly die of chronic diseases. In low-income countries, where less than one in five of all people reach the age of 70, and more than a third of all deaths are among children under 15, people predominantly die of infectious diseases.

An autopsy, also known as a postmortem examination or an obduction, is a medical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a human corpse to determine the cause and manner of a person's death and to evaluate any disease or injury that may be present. It is usually performed by a specialized medical doctor called a pathologist.

Autopsies are either performed for legal or medical purposes. A forensic autopsy is carried out when the cause of death may be a criminal matter, while a clinical or academic autopsy is performed to find the medical cause of death and is used in cases of unknown or uncertain death, or for research purposes. Autopsies can be further classified into cases where external examination suffices, and those where the body is dissected and an internal examination is conducted. Permission from next of kin may be required for internal autopsy in some cases. Once an internal autopsy is complete the body is generally reconstituted by sewing it back together. Autopsy is important in a medical environment and may shed light on mistakes and help improve practices.

A necropsy, which is not always a medical procedure, was a term previously used to describe an unregulated postmortem examination. In modern times, this term is more commonly associated with the corpses of animals.

Senescence refers to a scenario when a living being is able to survive all calamities, but eventually dies due to causes relating to old age. Animal and plant cells normally reproduce and function during the whole period of natural existence, but the aging process derives from deterioration of cellular activity and ruination of regular functioning. Aptitude of cells for gradual deterioration and mortality means that cells are naturally sentenced to stable and long-term loss of living capacities, even despite continuing metabolic reactions and viability. In the United Kingdom, for example, nine out of ten of all the deaths that occur on a daily basis relates to senescence, while around the world it accounts for two-thirds of 150,000 deaths that take place daily.